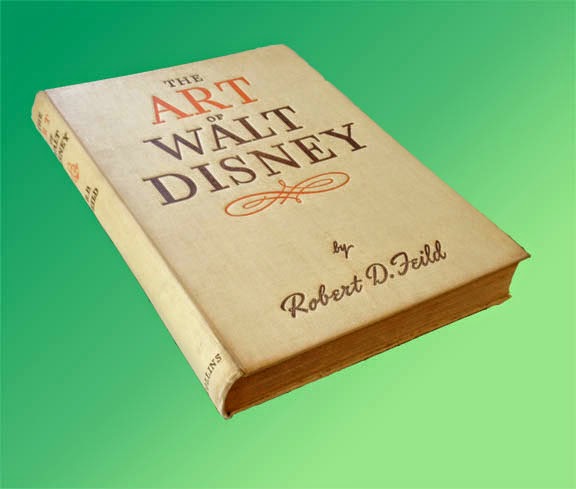

The Art of Walt Disney, by Robert D. Feild, 290 pages, pub. 1942 by Macmillan and Co.

First, you should understand that there are two completely different books called The Art of Walt Disney. The better known of these is the most recent, a massive coffee table book by Christopher Finch first published in 1974. In fact, when I went to Amazon just now to look at reviews of the earlier Art of Walt Disney, I found that all the reviews seemed to be of the 1974 book; all these people had no knowledge of the one published in the 1940s. But the Finch version, rich in color artwork but short on real information about the animation studio, was for me a vast disappointment.

The other book known as The Art of Walt Disney was published in 1942 and written by a professor of art who was given a year of access to the Disney studio in Burbank between 1939 and 1940. An interesting year it was, too, for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs had premiered successfully in 1937, proving the viability of feature-length animation and spurring the studio to initiate production on not one but several new features. The book therefore contains details on the production of Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo, all of which were in various stages of development, as well as many animated short subjects which were still a major division of production at Disney.

|

| Early concepts of the 7 dwarfs. Some of these are by Albert Hurter. |

As an art historian Feild admitted to a quandary about what the animated productions of the Disney studio actually meant as art, but he knew he was onto something big and exciting. Disney the producer had thrown far more money back into raising the standards of animation than he had kept for himself, and the result was a clear lead in production quality and standards over every other Hollywood studio. Efforts by other countries, from the Disney point of view, did not even exist.

|

| Layout sketches, possibly by Tyrus Wong. |

The book itself was the first serious literary survey of Disney or of any animation, and its publication was a tribute to the new recognition and respect accorded to Walt Disney after his sensational breakout from shorts starring Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Goofy into the world of feature films. For an exhilerating two years or so after the release of Snow White, anything seemed possible and the continued success of the studio seemed assured.

World war beginning in 1939 with Hitler's invasion of Poland ended all that, closing lucrative distribution markets in Europe and, after 1941, diverting much of the studio's energy into jingoist war propaganda. According to a 1942 review in Saturday Review, however, the book went to press before the December, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor, and so Feild's writing was not influenced by the direct involvement of America--and Hollywood--in World War II.

|

| These may be examples of Shamus Culhane's "fast animation" technique. |

There is an oft-told story of Walt Disney confronting one of his ambitious young artists back in the '30's, telling him not to get any ideas about making a name for himself at the studio; the only name the public was to see was that of Walt Disney. The story is true, though of course the features from Snow White on had artist credits just like any other feature films. But Feild in his book maintained Disney's attitude about keeping the artists anonymous, and so there is not a single animator or designer mentioned by name in the entire book. From the point of view of historical interest, this is an unfortunate omission, although subsequent writing over the ensuing decades has illuminated some of this darkness. One can easily recognize the work of Marc Davis, of Milt Kahl, of Rico LeBrun and others.

|

| Some of Preston Blair's dancing hippo drawings, made famous in his animation book. |

The text is written in a somewhat verbose style typical of the day, but the book does a good job of detailing the Disney production process and even makes an attempt to describe the intricacies of animating. Much is made of the expansive new Burbank production plant. Yet the refusal to name names continues to be an irritant throughout. Besides Walt, only Roy Disney is mentioned by name. How can you tell the story of Walt Disney without mention of Ub Iwerks? Of Ham Luske and Norm Ferguson and Bill Tytla and Freddie Moore? Yet Feild manages to keep them all behind the curtain, to the point that I suspect this anonymity was a precondition imposed on him by Walt.

|

| Uncredited like all the others, here are some structural guides for deer animation by Rico LeBrun. |

Nevertheless there are many full-page plates or illustrations, some in color, that make the book a worthwhile document of the Disney studio in the early 1940s.

|

| Animation drawings of Ali the alligator, very possibly by John Lounsberry. |

Feild's The Art of Walt Disney is considered a collector's item. My copy is a British reprint (1944) published in London by Collins. Copies available on the internet are few and not inexpensive, but it is still possible to get one if you want it badly enough.