As blogs go, Acme Punched! has only a small following. But, you are from all over the world! My stats show me that I have readers in Brazil, Ukraine, South Korea, Columbia, Egypt, Israel, Portugal, Australia, Indonesia, China, Great Britain, Sweden, Sudan, Saudi Arabia, India, Nigeria, and on and on. All the populated continents and all the island nations have people interested in hand-drawn animation, who have looked at my blog.

To me, it feels nothing short of awesome. Thanks for listening. I will try to keep doing this. To all of you I wish happy holidays in this time of the winter solstice (in the Northern hemisphere, that is!) and in this year-end time of renewal.

I wish for all the people suffering in the troubled parts of the world, in Yemen and Syria, in Iraq and Afghanistan and Nigeria, in Sudan and Pakistan, in Somalia and Ukraine and the Central African Republic, and in all places which are troubled by war and privation and the natural ravages of weather and earthquakes--I wish for all of them to have something to make them happy in the coming year, or at least to make them secure.

Here's a cartoon to make you laugh.

Best wishes for the New Year!

--Jim Bradrick

and Acme Punched!

Pages

For People Crazy About 2D Animation!

Acme Punched! is for people crazy about 2D animation. It may be enjoyed by beginners and others, but it is aimed at animators who know already something about the process of animation and the basics of character animation. In large part, it will attempt to provide a deep look into the problem solving that goes on in my head as I work out a scene, often in step-by-step posts that I will sometimes enter in "real time", without knowing in advance what the outcome will be. Mistakes and false starts will not only be included but emphasized, so that the creative process of animation will be portrayed realistically. And, while my own bias is for 2D drawn animation, many of the effects and principles discussed here can apply to CGI 3D animation as well. I hope the blog will prove useful and instructive for all.

-Jim Bradrick

-Jim Bradrick

Saturday, December 23, 2017

No. 145, Time to Detaxi, Part One

Dee-taxi?!

To disembark from a train is to detrain, so I am thinking perhaps detaxi might work for getting out of a car for hire.

In any case, we are getting my Old Man character out of his taxi in this next scene. He has arrived in front of the airport, and this scene is just before the one of the taxi driver moving the Old Man's trunk, which we looked at in posts 142 and 144.

Here are the storyboard panels for the scene.

By the time it came for the animator (me) to begin the key drawings that would supplant these panels by the storyboard artist (me), some things had changed. I had done careful layout drawings of the taxi with its interior, and animation of its door opening. And I had done a lot of thinking and study about what the action should look like, not excluding my getting in and out of the back seat of a car a number of times.

|

| The taxi interior. Of course the door is on its own layer. |

|

| The door, closed. |

|

| The door, all the way open. |

I decided I wanted both to show that the Old Man, though somewhat deformed in his back, had a lot of agility in spite of his handicap, and that getting out of the back seat of most cars is unavoidably awkward. (We are not thinking of older taxis from previous decades that were designed with extra leg room in the back seat.)

Here are some keys and extremes.

|

| He opens the door of the taxi. |

|

| He gets both hands braced. |

|

| Bringing out his left foot. |

|

| Ready to stand up, but we cut to a closeup here. |

A couple of pose drawings came hard to me, but I kept after it and they did finally get resolved.

Next I got them down on the exposure sheets, doing my best to time them out accurately so that they could be assigned drawing numbers and spacing guides. I have not always done this at this stage in animation but it is useful to learn to work out timing with a metronome beat or a stopwatch as I imagine each move from extreme to extreme. I own a classic wind-up stopwatch, but a digital stop watch is a standard feature on many cell phones. There are also a number of metronome apps that can be downloaded free.

|

| Analog and digital stopwatches. |

Here is a pencil test of the whole scene, first a rather dim version with two layers exposed, so that you can see how the character relates to the taxi.

And now, the same business with the character alone.

You can see that there are still some drawings missing, but it does look like it is working.

I will soon post the full pencil test, but not until after the first of the year.

Tuesday, December 5, 2017

No. 144, A Weighty Problem, Part 2

To answer the question posed at the end of Part 1 (No. 142, A Weighty Problem, Part 1), I believe that the animation works as intended.

The problem was that a beefy man, the Taxi Driver, was to pick up and move the Old Man's trunk, showing how very heavy it was. But the staging I had chosen did not show all the action--did not show the effort of the Taxi Driver lifting the dead weight of the trunk off the ground. The severely cropped staging was chosen to emphasize the trunk's size, and also to startle the viewer when the trunk is unexpectedly and violently set down to almost fill the screen.

But I was betting that the scene would work anyway if I carefully animated the Taxi Driver's effort in moving the trunk. Also I was counting on sound effects--the grunting and the impact of the trunk being set down hard--to help put across the man's effort.

Here is the final animation...

a

The right border of the screen is cropped in this pencil test at the same place where I intend to crop the finished shot. (See the storyboard panels in post 142.) As yet, there is no sound at all, but I am happy to see that the animation still has the power that I hoped for.

Sometimes now, I actually get things right on the first try.

Next: All About Getting Out of a Taxi

The problem was that a beefy man, the Taxi Driver, was to pick up and move the Old Man's trunk, showing how very heavy it was. But the staging I had chosen did not show all the action--did not show the effort of the Taxi Driver lifting the dead weight of the trunk off the ground. The severely cropped staging was chosen to emphasize the trunk's size, and also to startle the viewer when the trunk is unexpectedly and violently set down to almost fill the screen.

But I was betting that the scene would work anyway if I carefully animated the Taxi Driver's effort in moving the trunk. Also I was counting on sound effects--the grunting and the impact of the trunk being set down hard--to help put across the man's effort.

Here is the final animation...

The right border of the screen is cropped in this pencil test at the same place where I intend to crop the finished shot. (See the storyboard panels in post 142.) As yet, there is no sound at all, but I am happy to see that the animation still has the power that I hoped for.

Sometimes now, I actually get things right on the first try.

Next: All About Getting Out of a Taxi

Wednesday, November 29, 2017

No. 143, Help Fund "Mushroom Park"

Mushroom Park

|

I have been asked by Tim Rauch to help get the word out about the Kickstarter project "Mushroom Park". This is not only animated, it is hand-drawn, without any 2D puppet animation as far as I can see. The Rauch Brothers animation is loose and lively, a pleasure to watch. Looks to me like those guys are acme punched for sure!

As you know, Kickstarter requires that a project be pledged the full stated amount by the deadline date, or they get: NOTHING.

The good news is that they are 68 percent of the way there, with nearly $14,000 out of $20,000 pledged. But only 13 days remain to the deadline, so don't delay. Here is the Kickstarter link:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1994234025/mushroom-park-the-animated-film

Let's make this dream real!

Friday, November 24, 2017

No. 142, A Weighty Problem, Part 1

In the first sequence of my film Carry On, I want to establish not only how impossibly big the Old Man's trunk is, but how heavy as well.

My opportunity presents itself early on, when the trunk, having arrived at the airport entrance projecting from the boot of a taxi, has to be lifted out and set upon the sidewalk. Here are the storyboard panels for that action.

So perhaps you see right away the animator's problem here: it's what isn't being shown. We don't see the trunk being lifted, and we barely get to see the taxi driver at all. The audio will help out; there will be some grunting and groaning, and there will be a loud impact sound as the trunk hits the concrete.

But I was worried about trying to animate only the parts of the taxi driver framed by the camera here.

Solution? Animate the entire movement in rough drawings from beginning to end, just to make sure that I am really understanding all the physics involved.

It wasn't that hard. First I did a page of thumbnails:

Then, in little more than an hour, I banged out this test animation.

It is silent, it is missing a lot of detail, including squash and stretch on the trunk and some drawings that will be on ones, and yet it puts across the impression of tremendous weight. Even with the right half of the image masked off--the way it is framed in the storyboard--I can tell that it will work.

Next: I will go ahead and do final animation of the above action, and we will see if my confidence is misplaced.

My opportunity presents itself early on, when the trunk, having arrived at the airport entrance projecting from the boot of a taxi, has to be lifted out and set upon the sidewalk. Here are the storyboard panels for that action.

|

| The Old Man waits on the sidewalk. |

|

| The taxi driver's foot comes in from the right. |

|

| The big trunk swings into view. |

|

| The trunk lands heavily, with some squash and stretch. |

|

| The Old Man turns his head to regard the trunk. |

So perhaps you see right away the animator's problem here: it's what isn't being shown. We don't see the trunk being lifted, and we barely get to see the taxi driver at all. The audio will help out; there will be some grunting and groaning, and there will be a loud impact sound as the trunk hits the concrete.

But I was worried about trying to animate only the parts of the taxi driver framed by the camera here.

Solution? Animate the entire movement in rough drawings from beginning to end, just to make sure that I am really understanding all the physics involved.

It wasn't that hard. First I did a page of thumbnails:

Then, in little more than an hour, I banged out this test animation.

It is silent, it is missing a lot of detail, including squash and stretch on the trunk and some drawings that will be on ones, and yet it puts across the impression of tremendous weight. Even with the right half of the image masked off--the way it is framed in the storyboard--I can tell that it will work.

Next: I will go ahead and do final animation of the above action, and we will see if my confidence is misplaced.

Tuesday, November 14, 2017

No. 141, What's Inside: 2 More Pencil Tests

Continuing our work on scene 1-8, we continue to delve into...

Upon finally seeing the test with all the drawings in, I was not happy with the arm and hand movement. I had tried a very loose and gangly style, which I could now see was more appropriate for Art Babbitt's Goofy than for this old man. I could have just tried damping down the floppiness of the hands, but I thought that he might look good with an entirely different style, sort of gliding his hands back and forth with half-closed fists and with an elliptical pattern to the movement.

Here is how that came out.

Again I was disappointed, as the elliptical cycle was too pronounced. It gave off an impression of self-consciousness that was wrong. That is, the Old Man appeared to be aware of his own hands, which is not the effect I wanted. But I still liked the concept, so I simply flattened the ellipse, lowering the hands as they came forward.

Here is the pencil test with that correction.

I feel that this works well now. At the end of the scene, I also show his left elbow backing up; this makes a nice anticipation for the forward movement of his left hand onto the trunk.

* * * *

Pencil tests are so easy and fast to do, there is no reason not to do them. Nor is there any shame in it. Traditional animators are in the business of making something look alive out of a series of closely related images that are not alive. Much can be learned by experience, but the experience and the received knowledge from books and instruction are only aids that will help you to get close to what you want. For anything truly original, pencil testing your work and studying the result is the best way to get your animation to closely match the vision in your mind.

Floppy Hands and Arms

Upon finally seeing the test with all the drawings in, I was not happy with the arm and hand movement. I had tried a very loose and gangly style, which I could now see was more appropriate for Art Babbitt's Goofy than for this old man. I could have just tried damping down the floppiness of the hands, but I thought that he might look good with an entirely different style, sort of gliding his hands back and forth with half-closed fists and with an elliptical pattern to the movement.

Here is how that came out.

Pencil Test, Version 4

Again I was disappointed, as the elliptical cycle was too pronounced. It gave off an impression of self-consciousness that was wrong. That is, the Old Man appeared to be aware of his own hands, which is not the effect I wanted. But I still liked the concept, so I simply flattened the ellipse, lowering the hands as they came forward.

Here is the pencil test with that correction.

Pencil Test, Version 5

I feel that this works well now. At the end of the scene, I also show his left elbow backing up; this makes a nice anticipation for the forward movement of his left hand onto the trunk.

* * * *

Pencil tests are so easy and fast to do, there is no reason not to do them. Nor is there any shame in it. Traditional animators are in the business of making something look alive out of a series of closely related images that are not alive. Much can be learned by experience, but the experience and the received knowledge from books and instruction are only aids that will help you to get close to what you want. For anything truly original, pencil testing your work and studying the result is the best way to get your animation to closely match the vision in your mind.

Thursday, November 9, 2017

No. 140, What's inside: 3 Pencil Tests

Time for another episode of...

The Old Man Walks In and Stops

This is a short scene where the steamer trunk is sitting on the sidewalk; the Old Man walks up to it, stops, and places his hand on the top.

I have previously animated the Old Man twice in a walk. In the first, the walk is lopsided and under constant strain as he is dragging his trunk along behind him. In the second, he quickly walks off screen. This time I will show him full length, including his feet, so I am establishing a style for him that is to be his normal walk.

First I determined that it should take him 4 steps to get him from the starting pose to the end. Then, thinking that an old man might move slowly, I decided each step should be 16 frames, a little longer than the average 12 frames per step. Blocking that in, with only the contact and passing positions drawn, I did this first pencil test with 8 exposures per drawing; thus, with only 1/4 of the drawings done, I can nevertheless evaluate the rhythm of his steps, since each step is already at 16 frames; the timing is the same as the final animation will be.

This shows me that the general timing works and also that the mass and perspective are consistent and convincing.

The arm and hand movement here is experimental and, as you will see, required some more thought, but at the time of this test I was happy with it.

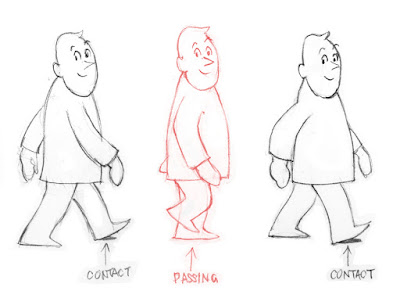

Contact and Passing Positions

This looks like a good time to review what is meant by Contact and Passing positions in a walk.

If you want to do a character walking, where do you start? Well, you start with an extreme, a drawing that illustrates the instant when an outstretched foot touches down to the ground: the contact position. (There are animators who prefer to start with the passing position, which is the point halfway between the left and right contacts.) The passing position tends to be undramatic as a silhouette, with one leg passing in front of the other and with both arms more-or-less even with the body. The passing position is the breakdown between the extremes of the left and right contact positions.

1

Not a Standard Walk Cycle

Note that this walk is not a repeatable cycle since the Old Man is turning as he walks and the drawings could not be properly looped. A good working method here might be to first do an actual repeatable cycle as a reference, then extrapolate from those drawings as the camera or the character turns in perspective. I did this once with a running character where the effect was that the "camera" swooped up and over the runner until we were looking straight down on him. It worked, but in this case, with just a small turn involved from 3/4 front to 3/4 rear, I felt I could do it without that preliminary cycle.

More Drawings

Next I filled in one drawing between each existing pair. I now make a new pencil test, exposing each drawing for 4 frames, which maintains the same timing as before. Here is a section of the pencil test exposure sheet for both the first and second tests. (With my pencil test software, Toki Line Test, I can put all the versions of the pencil test into one file, with each version on a new layer. All layers except the one I want to view or to output as a Movie can be turned off. Probably this is possible with other software as well.)

|

| Here, the A column shows the first test, while the B column shows the second. You can see how the position of drawing 9, for example, begins both times at the same frame. |

All the Drawings

Everything still seems to be working, so I push on and add all the remaining drawings. For the walk, that means one more drawing between each existing pair. (The section at the end of the scene, after he stops and when he places a hand on the trunk, is more complex than this.)

It is time for a third pencil test, and now that all the drawings are in, we shall have a complete idea of the movement, even if some drawings are still quite rough.

Here again is a part of the exposure sheet, with this test represented in column C.

|

| With all the drawings now present, you can see that each drawing in column C has only 2 exposures and, again, drawing 17 begins on frame 17. The three pencil tests are all the same length. |

Next: Fixing What Is Not Right

Saturday, October 28, 2017

No. 139, What's Inside, 2: The Gadget, Part Two

The Numbers Racket

|

| Depending on what changes are made, a drawing number might eventually return to its original designation! |

In 3D animation, the frame or image numbers are counted for you, more or less, so if you make a change in timing, your computer just resets the numbers. (Haha! If I am wrong about this, I expect some of you with more experience in 3D than I have will set me straight.)

Animating on paper, your drawings must be hand-numbered and those numbers must be entered on your (paper) exposure sheet. Later on, beyond scanning, your pencil test or animation program such as Animate Pro will track further changes. Before that, however, it is pencils and erasers.

|

| Actual re-numbered drawings. |

I confess that I have to use erasers for renumbering quite often. It is a simple matter of lack of experience. Perhaps you find that surprising, but my career experience compared to that of, say, a Ken Harris at Warner Brothers, is insignificant.

Consider that a Hollywood studio animator in the 1940s or 1950s would turn out up to 30 feet of animation a week. That's 20 seconds. He was responsible only for timing and extreme and breakdown drawings, and for making spacing guides for his inbetweener. In some situations, timing was already worked out by the director. And the animator worked at this week after week, year after year. It got to the point where such an animator would look at a scene and know instinctively and accurately how long a hold should be, or how short. Thousands of career hours "on the board".

Compare that to the independent animator like me, who also has had to perform all the other job titles that animation production entails--storyboarding, layout, inbetweening, digital ink and paint (and, oh yes, actual ink and paint on cels until the 1990s), background art and camera work--and you can see that my actual time spent "on the board" doing animation was but a small fraction of my total effort. What would be my footage count in a week? Averaged out, it would certainly be less than one foot.

Factor in also all the down time: time spent looking for new accounts, time waiting for contracts to be signed, time working at some day job when the animation work just wasn't there.

Is it any wonder that for all that I do know, I sometimes get it wrong when I try to time out in advance how long the Old Man should gaze into the darkness of his trunk before turning back to look at the guards? Not enough flying time; not enough hours "on the board."

Thus, I erase, renumber drawings, and sometimes have to renumber them again. I elect to use a 12-frame hold, then see in pencil test that 16 or 20 frames is better. Some other hold is too long and gets shortened. Yes, it is mostly changes in the duration of holds that causes my numbering changes. I need more experience "on the board."

But I'm working on that.

[Note: I use the Disney numbering system which links the drawing number directly to the frame number in the scene. Thus, if you add or subtract drawings or change an exposure length, all the subsequent numbers are thrown off. This is, admittedly, an awkward system for someone not yet sure of all timing.]

And while I'm on the subject of timing, let me tell you about...

The Hold that Isn't There

Before continuing, please go back to post 138 and play the video again. Look for the part where the Old Man, after himself looking into the trunk, straightens up a bit and looks back to the right before plunging his hand in to get the cylinder.

Do you see the hold there? Right at the top of the action, right before he turns back to the trunk? No?

Well, there was a hold there. It was just 6 frames long, right on this drawing here.

|

| The drawing that was held for 6 frames. |

I had been very deliberately experimenting with a moving hold there, getting the Old Man's head turned early in the move so that the pose of him looking to the right would read without actually holding on one drawing. Then, before testing it, I lost my nerve and added in that 6-frame hold. (Which affected the numbering from that point on.) It did look okay that way, but later, remembering my original idea, I took that hold out--reducing the exposure on that drawing from 6 frames to 2, actually--and found that it still worked quite well.

Lesson learned: with 8 drawings or sixteen frames, closely spaced, all showing his head looking to the right, no actual held drawing is necessary. What about 14 frames or 12 or 10? Will the pose still read? Maybe. Every situation, every animation scene, is different. You can always do a pencil test.

Saturday, October 21, 2017

No. 138, What's Inside!, 1: The Gadget, Part One

Where have I been?

|

| Me at St. Michael's Mount, Cornwall. |

Now that I have reached the actual animation stage of my film production of Carry On, I find it appropriate to try to detail all the thinking and planning that go into many of the scenes I will be animating. I am now calling this type of post "What's inside!".

"What's inside" means all the things that the animation includes in terms of drawing, timing, spacing and any other aspects of the animation process that can be explained, and also the missteps and changes that take place before the scenes are finally approved.

I'll start with a scene I have referenced before, scene 6-15, where the Old Man opens his trunk and pulls out a cylindrical device which he then holds out for the guards to see. I am still working on this and have made some changes in the last few days.

First, here is the latest version:

A Puzzle

I have a lot to say about this scene, but first I have a fun puzzler for you. I challenge you to compare the latest version with this slightly older one and then say what change in animation has been made between them.Don't be distracted by the more complete drawings in the new one--that isn't what I am talking about. If you can see what I mean, contact me and I will send an original drawing to the first two people who get it right.

Getting into What's Inside!

Okay, I have already showed you (in post No. 137) how I animated some of the legs in a second pass.Now lets look at the movement where the Old Man, beginning with his hand inside the trunk, lifts the cylinder out and then turns and holds it out toward the guards. This movement required 29 drawings on two's, so it lasts 2 1/2 seconds up to the hold at the end.

Simple? Not quite. There are really only two key drawiings: the first and the last. (Remember, key drawings are the drawings that tell the story.)

|

| The two Key or story-telling drawings, 163 and 235. |

But clearly I needed more extremes than that, because, for one thing, how are you going to chart 27 inbetweens? That might look like this!

Also, the change from one key to the other is enormous, so a little control is necessary, and you get that by defining the move with some more extremes plugged in.

I did this by animating more or less straight ahead between the keys and, working rough, produced three extremes.

|

| The added Extremes/Breakdowns: 195, 207 and 223. |

A major example of this in scene 6-15 is what happens with the head relative to the hand holding the cylinder. I decided that I wanted the cylinder to arrive sooner than the head to its final position, because the whole point of this action here is to get the cylinder out and display it to the guards. If you play the scene, you will see that the head arrives late and catches up with the left hand. This was easily done by simply showing the cylinder almost to the end of its arc by breakdown drawing 223, a full seven drawings before the hold.

|

| Drawings 223 and 235. His left hand in the first drawing is in the final ease-in, while the head still has far to go. |

|

| Here you see the same two drawings in register, making the situation more clear. |

To be continued in post no. 139...

Sunday, August 27, 2017

No. 137, Taking Steps Without Legs

I think I have touched upon this before, but it is an amazing thing that really does work: you can in some cases animate a character moving from one place to another, without drawing the legs or feet at all until the very end. And yes, I mean in a full figure scene that shows the legs and feet.

I just did it again in a scene I am animating, and even though I have done it before, it always requires a leap of faith to try it--to keep myself from blocking in the lower limbs. Because, after all, doesn't that leave the head and upper body just hanging there in space? How can that ever come out right? I ask myself.

Well, it certainly does take some planning.

In my experience, you will want to know the precise perspective of the layout involved. You will want to be sure you understand your character's relation to that perspective. And you will want a solid key drawing--with legs and feet--both before the movement and at the end.

The fact is, when we step over from one position to another on the floor, we do not always bounce noticeably up and down with each step. Walk cycles are usually full of the up and down movement of the body mass, sometimes with a lot of squash and stretch to add weight to the character. But like good dancers, we sometimes shift our position in a way that is more smooth and gliding, and the usual bobbing up and down is then unnecessary and even distracting.

Let's look at the scene to which I am referring. My Old Man character has just opened up his steamer trunk. Aware that he is being watched by security guards off the right side of the screen, he reaches into the trunk and pulls out a cylindrical object which he then holds out for the guards' inspection.

I did not start this scene with the intention of using the "no legs" technique; it just became appropriate in my mind when I saw that as the Old Man lifts out the cylinder, he must take two (or three or four) steps as he turns almost 180 degrees and holds the object out. This move was to be done slowly with a moving hold at the end, involving 30 drawings on 2's and over 2 seconds.

As I began roughing in the extremes of this move, there were other complexities to think of, as for example that I wanted his hand with the cylinder to arrive first while his head and torso catch up a bit later. So I began leaving his legs and feet completely off the extreme drawings between no. 161 and the last drawing, no. 233.

Even as I filled in the breakdown drawings and all the inbetweens, I did not think about the legs and feet. His torso simply turned in midair, drifted across a little way, and came to rest at drawing 233, where he had his legs and feet once again.

And note this: none of those three contact drawings was an extreme pose as regards the upper torso. This is fine, but to me the significance of that is that had I tried to do the legs and feet at the same time as the turning torso, I would no doubt have tried to force the contact drawings onto some of the existing extremes. That might have worked out anyway, but it might also have resulted in something more stilted, less fluid, and less interesting to watch. Using this technique, I was completely free to place the contact drawings wherever seemed best, rather than just on one or another of the available extremes, since by this method all the drawings already existed.

Here is the link to the video. This is not the whole scene but just the end of it.

This post serves as a reminder that it is often wise to make several passes over a scene, doing things one at a time, rather than struggle with the complexity of trying to get everything in all at once.

By the way, I am certainly not the first to think of doing this. It is mentioned somewhere in Thomas and Johnston's Illusion of Life; when I locate the reference, I will amend this post with the details.

I just did it again in a scene I am animating, and even though I have done it before, it always requires a leap of faith to try it--to keep myself from blocking in the lower limbs. Because, after all, doesn't that leave the head and upper body just hanging there in space? How can that ever come out right? I ask myself.

Well, it certainly does take some planning.

In my experience, you will want to know the precise perspective of the layout involved. You will want to be sure you understand your character's relation to that perspective. And you will want a solid key drawing--with legs and feet--both before the movement and at the end.

The fact is, when we step over from one position to another on the floor, we do not always bounce noticeably up and down with each step. Walk cycles are usually full of the up and down movement of the body mass, sometimes with a lot of squash and stretch to add weight to the character. But like good dancers, we sometimes shift our position in a way that is more smooth and gliding, and the usual bobbing up and down is then unnecessary and even distracting.

Let's look at the scene to which I am referring. My Old Man character has just opened up his steamer trunk. Aware that he is being watched by security guards off the right side of the screen, he reaches into the trunk and pulls out a cylindrical object which he then holds out for the guards' inspection.

I did not start this scene with the intention of using the "no legs" technique; it just became appropriate in my mind when I saw that as the Old Man lifts out the cylinder, he must take two (or three or four) steps as he turns almost 180 degrees and holds the object out. This move was to be done slowly with a moving hold at the end, involving 30 drawings on 2's and over 2 seconds.

As I began roughing in the extremes of this move, there were other complexities to think of, as for example that I wanted his hand with the cylinder to arrive first while his head and torso catch up a bit later. So I began leaving his legs and feet completely off the extreme drawings between no. 161 and the last drawing, no. 233.

|

| Here are the extreme drawings nos. 161 at the beginning and 233 at the end. |

|

| The X-sheet, showing where I decided to place the contact drawings. Scenes like this should not be attempted without charting your timing on an X-sheet first. |

And note this: none of those three contact drawings was an extreme pose as regards the upper torso. This is fine, but to me the significance of that is that had I tried to do the legs and feet at the same time as the turning torso, I would no doubt have tried to force the contact drawings onto some of the existing extremes. That might have worked out anyway, but it might also have resulted in something more stilted, less fluid, and less interesting to watch. Using this technique, I was completely free to place the contact drawings wherever seemed best, rather than just on one or another of the available extremes, since by this method all the drawings already existed.

|

| Now these lowly inbetweens have become extreme contact drawings for the leg movement |

Here is the link to the video. This is not the whole scene but just the end of it.

This post serves as a reminder that it is often wise to make several passes over a scene, doing things one at a time, rather than struggle with the complexity of trying to get everything in all at once.

By the way, I am certainly not the first to think of doing this. It is mentioned somewhere in Thomas and Johnston's Illusion of Life; when I locate the reference, I will amend this post with the details.

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

No. 136, Animatic Reviews

Back in Post No. 128, Animatic Private Viewings, I described my animatic review process. To a select group of associates, I had sent a link to the full animatic of my film Carry On, asking for reactions to the film as a whole. The animatic, a filmed and timed version of a complete storyboard, augmented with an audio scratch track that includes dialog, sound effects and some music, can be a most valuable tool for the film maker, helping him or her to see the strengths and weaknesses in the story structure, in character development, and in other areas--things that are not so apparent when one is focussed on just one detail or moment at a time.

But to reach this stage in production also provides an opportunity for gathering opinions from outside one's own consciousness. In the case of the independent film maker, without even a production staff off whom to bounce ideas and from whom to gather opinions, the value of some more objective opinion is even more important.

I got back written reviews from just four people. That is fewer than I had hoped for but it was a good

sampling.

No one hated it and they all liked at least parts of it.

Three of the four liked it a lot but had widely differing suggestions for changes, and no two people wanted to change the same exact things.

No one came up with a genius idea that allowed me to cut whole minutes while still telling the whole story.

There were several thoughtful explorations along the lines of "what if a certain character were more like this or that."

They all brought up issues that I had already struggled with and had set aside as either irrelevant or as requiring adding more or completely different scenes to the film. There were also a few instances where the character or scene existed for a logical tactical reason which my reviewer had not perceived. For example, there is a scene with two characters whose only raison d'etre is to conceal the Old Man and his trunk from the view of the gate attendant until the last possible moment.

I am grateful for all the suggestions even if I don't use many of them. But there was one objection which troubled me a lot and has made me decide to re-write two of the sequences, replacing a major character, even though that involves quite a lot of work.

I had written in a character who could be perceived as a cultural slur. If you are a regular reader of this blog, you will recognize him from some posts about character design that I did a while back. He is the one for which I created a head-and-shoulders maquette out of Sculpey.

I was bothered not only because one reviewer strongly disliked the character but because my wife had expressed a similar dislike. (Some other reviewers did like Kevin for his strong comedy value.) And in my heart I didn't feel strongly attached to this character as I did to all the others in the film. In fact, I recognized that the character was artificial, conceived to advance the story as a person who had to provide a certain amount of resistance to letting the Old Man get past him, but who would then capitulate. He was a comic character, but comedy based too much on cultural stereotypes is unnecessary and unwise; I realized that a characterization that could be perceived as demeaning in this way would be shameful to have in my film.

And so, after much thought, I created another character who could fulfill the same purpose as Kevin had, but with different motives. He is actually better developed than the first one; he has a believable back story and a better relationship with the supervisor character with whom he interacts. It was a struggle to back myself up and re-think the two sequences that are involved, but I am now comfortable with the result.

The lesson here is that nothing in your work should be considered immune from change if the reason for change is a strong one. Walt Disney knew this when he cut two already-animated sequences from Snow White. We should all remain open to the possibility of change even when it is painful.

But to reach this stage in production also provides an opportunity for gathering opinions from outside one's own consciousness. In the case of the independent film maker, without even a production staff off whom to bounce ideas and from whom to gather opinions, the value of some more objective opinion is even more important.

I got back written reviews from just four people. That is fewer than I had hoped for but it was a good

sampling.

No one hated it and they all liked at least parts of it.

Three of the four liked it a lot but had widely differing suggestions for changes, and no two people wanted to change the same exact things.

No one came up with a genius idea that allowed me to cut whole minutes while still telling the whole story.

There were several thoughtful explorations along the lines of "what if a certain character were more like this or that."

They all brought up issues that I had already struggled with and had set aside as either irrelevant or as requiring adding more or completely different scenes to the film. There were also a few instances where the character or scene existed for a logical tactical reason which my reviewer had not perceived. For example, there is a scene with two characters whose only raison d'etre is to conceal the Old Man and his trunk from the view of the gate attendant until the last possible moment.

I am grateful for all the suggestions even if I don't use many of them. But there was one objection which troubled me a lot and has made me decide to re-write two of the sequences, replacing a major character, even though that involves quite a lot of work.

I had written in a character who could be perceived as a cultural slur. If you are a regular reader of this blog, you will recognize him from some posts about character design that I did a while back. He is the one for which I created a head-and-shoulders maquette out of Sculpey.

|

| Two drawn angles of Kevin, and his unfinished maquette. |

I was bothered not only because one reviewer strongly disliked the character but because my wife had expressed a similar dislike. (Some other reviewers did like Kevin for his strong comedy value.) And in my heart I didn't feel strongly attached to this character as I did to all the others in the film. In fact, I recognized that the character was artificial, conceived to advance the story as a person who had to provide a certain amount of resistance to letting the Old Man get past him, but who would then capitulate. He was a comic character, but comedy based too much on cultural stereotypes is unnecessary and unwise; I realized that a characterization that could be perceived as demeaning in this way would be shameful to have in my film.

And so, after much thought, I created another character who could fulfill the same purpose as Kevin had, but with different motives. He is actually better developed than the first one; he has a believable back story and a better relationship with the supervisor character with whom he interacts. It was a struggle to back myself up and re-think the two sequences that are involved, but I am now comfortable with the result.

|

| Examples of the facial expressions inspired my my new character, Howard. |

The lesson here is that nothing in your work should be considered immune from change if the reason for change is a strong one. Walt Disney knew this when he cut two already-animated sequences from Snow White. We should all remain open to the possibility of change even when it is painful.

Saturday, July 15, 2017

No. 135, The Subliminal Anticipation

Subliminal

The word means "below the level of consciousness" and was applied in the 1950s to images in advertising that were intended to influence the viewer without that viewer realizing what he had seen.

This might be an erotic image or other suggestive content cleverly inserted into a photograph or a single frame of film in a TV commercial. The single frame might be the words "BUY THIS!" Whether it was actually effective in marketing remains questionable.

In animation, I am coining the term subliminal anticipation to cover a technique described by Richard Williams in his book The Animator's Survival Kit. Williams doesn't use the word subliminal, instead referring to Invisible Anticipations on page 283 of his book (the first edition.)

Like most of the tips and tricks Williams describes, this is a subtle trick learned from Hollywood animators from the Warners and Disney studios to whom he "apprenticed" himself in the 1970s and 80s.

Unlike the obvious anticipations with which most of us are familiar, such as the windup of a baseball pitcher before the pitch--easily the most drawn-out anticipation example that I can think of--, the subliminal anticipation happens so fast that it isn't actually seen, but only felt. The images of the anticipation are shot on ones rather than twos (in terms of 24fps film speed), faster than the eye can register, and yet as Dick Williams puts it, they add a "snap" to an action that can be most effective.

I used this technique before an accented syllable in the dialog animation being analyzed in posts 132, 133 and 134 of this blog. As he speaks, the Old Man is lowering his head. One an accent, his head suddenly jerks upward and begins descending again on a new path. Before the accent is where I inserted two frames of subliminal anticipation.

First, let's look at a simplified example of the anticipation and accent using only a simple ellipse as the object.

Now, here is the same effect employed in dialog animation of the Old Man from my film in progress, Carry On. I used this subliminal anticipation technique on both the syllable accents (IN-ternet and FA-il.)

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

No. 134, Let's Talk!, Part 3

In my last post, No. 133, you saw the first rough pencil test for a short scene of dialog from the Old Man.

Filling in more drawings, I stopped to do a second test. Perhaps I could have skipped this one but with digital scanning and playback, an extra pencil test takes only a few minutes of time.

A lot has been smoothed out here; no surprises. All that is needed now is to get the rest of the drawings in and check it one more time.

Here is the final pencil test that includes all the drawings.

Notice the accents on "IN-ternet" and on "FA-il."

I had just reviewed Dick Williams notes on accents in dialog in his Animator's Survival Kit, and I think I made good use of the technique. There is something else I included in those: subliminal anticipations; that is, anticipations that are "felt" rather than "seen."

Next: Subliminal Anticipations Explored

Wednesday, June 7, 2017

No. 133, Let's Talk! Part 2

Working with the Soundtrack

For the Old Man's dialog for this scene, I have a four-second track to work from. Here is the sound clip with the accompanying storyboard panel.Key Drawings

Beginning the animation, I made several key drawings--the drawings that best represent the style and spirit of the animation. As is often the case, my key drawings are also some of the extreme drawings in the scene. But a key drawing may not always be used as an extreme, as for example the storyboard image above, which puts across the idea without actually being useful as an extreme.

|

| The scene's initial pose. Note that this is a rough. |

|

| Another rough. He is saying, "You never know..." |

|

| Here, a cleanup, where he is saying "fail." |

First Pencil Test

The scene will amount to about 50 drawings when done. In the first pencil test, I have done only 28 of those drawings, but I am able to time it out to the soundtrack by adding extra hold frames wherever there are drawings missing.

We are using the Disney studio numbering method which specifies that if you are working on two's (two exposures per drawing), then beginning with 1, all the drawings will have odd numbers. Therefore, a sequence on two's would be 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15. If I have drawn only numbers 1, 3, 7, 13 and 15, then I expose the pencil test as follows:

Drawing 1, two frames.

Drawing 3, four frames (includes two frames to account for number 5 which is missing.)

Drawing 7, six frames (includes two frames each for numbers 9 and 11, which are missing.)

Drawing 13, two frames.

Drawing 15, two frames.

When you then play the pencil test, there will be some jerkiness but it is possible to match the dialog to the images and see how the action flows. In this case, there were a couple of areas where it was critical to see the full action, and where I therefore made sure to add in roughs of all the drawings.

Here is that first pencil test.

Next: A second pencil test in which many more drawings are present, and then a final test including all of the drawings.

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

No. 132, Let's Talk!

When I began this blog in 2012, the project I was working on and drawing from for the blog posts was all in mime, without a word of dialog. So there were many posts about various kinds of animation, from walk cycles to surprised takes to getting a little fox out from under a tight-fitting hat. The posts are all still there if you want to go look them up.

But now that I have switched projects to the current one, Carry On, I can do something not covered before at Acme Punched. Now that I have characters who speak on camera, I can do some posts about animating dialog.

I actually love animating a good character whose words have been recorded by a skilled voice actor. And in one way, this sort of animation is made easier because much of the timing has been established by the actor; the timing leaves all manner of hints as to how to proceed.

Easier, but not easy. This does not free the animator from the need to do a lot of the acting himself, getting the gestures and body language to do justice to the voice acting. Indeed, the better the voice acting, the more I feel an obligation to match its quality with my animation.

The scene with which I am dealing is a medium closeup of the Old Man saying just one line, and it took only a single panel to illustrate the scene in the storyboard.

"You never know," warns the Old Man, "when the internet may fail!"

Next you will see the first key drawings for the scene. We will follow the animation through to the end and, eventually, see it in color.

But now that I have switched projects to the current one, Carry On, I can do something not covered before at Acme Punched. Now that I have characters who speak on camera, I can do some posts about animating dialog.

I actually love animating a good character whose words have been recorded by a skilled voice actor. And in one way, this sort of animation is made easier because much of the timing has been established by the actor; the timing leaves all manner of hints as to how to proceed.

Easier, but not easy. This does not free the animator from the need to do a lot of the acting himself, getting the gestures and body language to do justice to the voice acting. Indeed, the better the voice acting, the more I feel an obligation to match its quality with my animation.

The Old Man Speaks

The scene with which I am dealing is a medium closeup of the Old Man saying just one line, and it took only a single panel to illustrate the scene in the storyboard.

|

| The single storyboard panel that represents this scene. |

"You never know," warns the Old Man, "when the internet may fail!"

Next you will see the first key drawings for the scene. We will follow the animation through to the end and, eventually, see it in color.

Saturday, May 20, 2017

No. 131, Any Resemblance is Coincidental

There used to be a disclaimer appended to many movies and TV shows: "Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental." There were variations, but the intent was to indemnify a company from the possibility of a lawsuit; if resemblance to a living person was suspected, this statement was supposed to categorically protect the author or film makers.

A couple of weeks ago, at the time of organized demonstrations against climate change denial, I saw this photograph of a renowned ninety-seven year old scientist named Eddy Fischer, a past winner of the Nobel Prize.

Of course, I was struck by Mr. Fischer's resemblance to my Old Man character in Carry On, my animated film now in production. But I hereby deny that the Old Man's uncanny resemblance to an old man named Eddy Fischer is anything other than coincidence.

A couple of weeks ago, at the time of organized demonstrations against climate change denial, I saw this photograph of a renowned ninety-seven year old scientist named Eddy Fischer, a past winner of the Nobel Prize.

|

| Photo by Alan Berner and The Seattle Times |

Still, despite Mr. Fischer having some hair and a back that is not deformed, it is an amazing resemblance, don't you think?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)